On 18 December, NHS England quietly published the report of Dr David Levy’s review of adult gender clinics. The report’s official title is the massively dry Operational and delivery review of NHS adult gender dysphoria clinics in England, but it’s commonly referred to the “Levy Review” within community spaces.

Prior to its publication, there were some concerns about the Levy Review being a sort of Cass Review for adults, leading to further massive restrictions in trans people’s access to healthcare. I witnessed active catastrophising in some quarters, with social media posts calling medication stockpiling. I don’t think this kind of rollback was ever on the cards with Levy, but I do understand why people were concerned. Trans people’s trust in the NHS and political processes is – justifiably – at rock bottom.

There were also a minority who hoped that the Levy Review might result in significant improvements to how trans people are treated by the NHS in England. I don’t think that was ever realistic either.

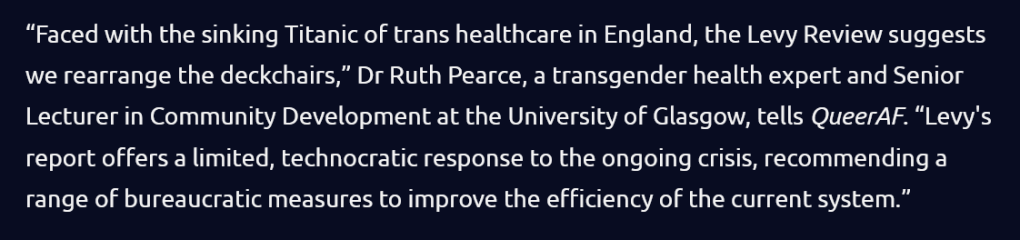

In reality, Levy does acknowledge some of the problems with English gender clinics, focusing especially on capacity issues, inefficiencies, and long waiting times. It offers a series of recommendations relating largely to the practical operation and delivery of gender services (the hint is in the title!) QueerAF asked me what I thought about it for their coverage of the Levy Review, and I told them this:

These measures may still result in a few improvements. NHS England hope Levy’s recommendations will contribute to “clinical effectiveness, safety, and experience”. I am not entirely convinced. But perhaps the waiting lists can be a bit shorter and fairer, especially with the opening of new clinics and introduction of a national waiting list.

Why is the Levy Review like this?

Levy did not truly seek to understand, let alone confront, the real scope of the problem in trans healthcare services, sticking instead to the very narrow scope of the brief provided by NHS England. Deeper issues he ignored include open discrimination from healthcare practitioners, as well as gatekeeping, pathologisation, and dehumanisation baked into the design of the gender clinics. These all harm patients, while also wasting clinical time and resources.

When I started my PhD on trans healthcare in 2010, such issues were not widely understood outside of certain trans community settings. That is no longer the case.

There have been multiple reviews and consultations undertaken by NHS England over the past 15 years, including in 2012, 2014-2015, and 2017-2019. There was also a review undertaken by the House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee in 2015.

Then there’s the research I undertook for that PhD, later published in my book Understanding Trans Health. Here, I argued that long waiting lists for gender clinics are not simply a result of underfunding or bureaucratic inefficiencies, but also an inevitable outcome of the gatekeeping system. By positioning trans healthcare as a specialist matter, and forcing patients to prove over and over again in psychiatric evaluations that they are “really” trans, you create unnecessary roadblocks and bottlenecks for care.

There have been a lot of other studies undertaken since. The most notable might be the massive, rigorous, and extremely detailed final report of the Integrating Care for Trans Adults (ICTA) project, published in 2024. This was funded by the UK government through the National Institute for Health Research, and has been roundly ignored by NHS England.

There are also a growing number of popular analyses: blog posts, news stories, podcasts, and video essays. One prominent example is I Emailed My Doctor 133 Times: The Crisis In the British Healthcare System, by Philosophy Tube, which has been seen by over 2.5 million people to date.

All this research and commentary highlights those same problems ignored by Levy: discrimination, gatekeeping, pathologisation, and dehumanisation.

My feeling is that neither NHS England nor Levy were interested in these issues. In fact, they are not really interested in understanding trans people at all.

It is therefore no surprise that Levy not only ignores widely-documented problems, but also repeats factually inaccurate claims, such as that the growth in patient demand for gender clinics is “not well understood”. Quite aside from what we have learned from all of the research and commentary noted above, this growth was forecast back in the 2000s by the education and advocacy organisation GIRES, in a study funded by none other than the Home Office.

The really bad stuff (and how to protect your data)

For all the limits of the Levy Review, I feel most of the recommendations are somewhat positive and may help people a bit. On balance, it’s mostly okay.

However, there are a few real points for concern.

Firstly, Levy argues that a first assessment for medical interventions should always be undertake by a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist. As all the research on trans healthcare services has shown time and time again, this is both unnecessary and unhelpful. It compounds the pathologisation of trans people, wrongly positions trans healthcare as a “specialist” matter, and creates expensive bottlenecks for treatment.

Secondly, Levy insists that gender clinic patients should be referred by GPs, and should not be able to self-refer. This is intended to help with the problem of patients ending up on a waiting list with no information for clinical staff on who they are, what they are looking for, and what their healthcare needs might be. However, the recommendation ignores the widespread issue of transphobic GPs refusing to provide referrals, as well as the fact that not everyone will have a GP (see, for example, the fact that trans people disproportionately experience homelessness, or that we are more likely to avoid healthcare providers due to justified fears of abuse). The problem Levy is trying to address could have been tackled in a more sensitive way, for example through NHS England providing a short referral form that prospective patients can fill in when seeking an appointment at a gender clinic.

Finally, there is the issue of future research. Citing Alice Sullivan’s transphobic report on sex and gender, Levy calls for more data collection on patient outcomes. Here Levy fails to acknowledge the urgent need to build trust before trans patients can be confident the NHS will not misuse our data. Moreover, as Trans Safety Network have noted, NHS England have committed to addressing this through expanding the role of the National Research Oversight Board for Children and Young People’s Gender Services. Trans Safety Network report that the board includes members associated with anti-trans medical groups, including the Society for Evidence-Based Medicine (SEGM), who are listed as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, and CAN-SG. It’s little surprise therefore that the National Research Oversight Board has recommended that clinicians working with young trans people attend SEGM and CAN-SG conferences, ensuring the further spread of transphobic disinformation, pseudoscience, and hate.

Trans Safety Network therefore recommend that trans patients in England opt out of their healthcare data being used for research. They provide the following advice on opting out:

This can be done via the following links, the first to stop GP records being shared and the second to stop secondary care records being shared.

We also suggest you email your GIC the following to ensure your opt-out is clear and ask to have a note of this added to your care record. I do not give my permission for any aspect of my patient data to be submitted to, or collected for, the purpose of any research or non local audit without my express permission in writing being obtained in advance.

Emails should include your name, DOB and NHS Number to assist your GIC admin in finding your record. If you have been referred but not been seen by a GIC, you can still contact the GIC you were referred to.

Could it be better?

The failings of the Levy Review are not inevitable. There are numerous international models of better practice. For a strong example, see the Professional Association for Transgender Health Aotearoa’s 2025 Guidelines for Gender Affirming Care in Aotearoa New Zealand. This recommends treatment under an “informed consent” model. Here is some of their guidance on this for adult patients:

Being transgender is not a mental illness, and it does not impair capacity to consent to treatment. If a doctor or nurse practitioner has sufficient knowledge, skill and professional scope to initiate GAHT [gender-affirming hormone therapy] in an adult patient:

– There is no requirement for all people to be assessed by a mental health professional prior to starting GAHT

– For many transgender adults, GAHT can be initiated in primary care, without the involvement of secondary or tertiary care.

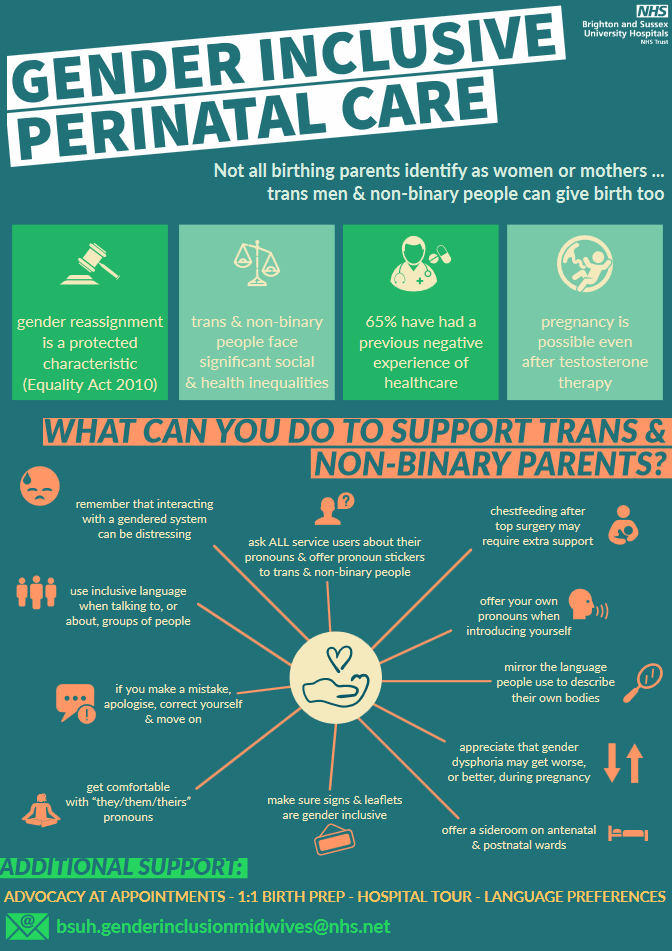

But we need not even look overseas for better. The Welsh Gender Service has seen a growing shift towards the provision of hormone therapy for trans people in primary care settings, supported through close collaboration with community organisations and GP practices. This has proven to provide a better experience for trans patients and has improved the efficiency of the service from an NHS perspective. The ICTA reportdescribes what this looks like in practice.

Case Study 4 in Chapter 4 reports on the establishment and initial development of regional primary care clinics, spread across Wales, which take responsibility for prescribing and monitoring HRT for trans adults following assessment at the specialist gender clinic. This is the most significant initiative we studied to address lack of integration between an assessing gender service and arrangements for prescribing and monitoring HRT. The key features are as follows. Their effectiveness and efficiency would appear to be of wider relevance to other gender services and NHS primary care commissioners.

The regional clinics were largely staffed by GPs, located within established GP practices and funded by the local NHS. They took responsibility for prescribing hormones, monitoring blood tests and titrating doses immediately following assessment, aiming to pass service users on to their usual practice after around 12 months, on the basis that their doses and prescriptions would by then be stable. This arrangement avoids the costly and damaging difficulties in communication between GICs and primary care practices over blood tests and dosage changes, experienced by many people attending other GICs. It also frees up gender specialists to devote more time to assessments, rather than review appointments for people already on hormones. Local clinicians, however, worked in an integrated way with their specialist colleagues, attending joint training on trans health care, and holding regular joint clinical consultations.

Further advantages emerging from this arrangement include the regional clinics rapidly becoming established as having GPs confident in prescribing under shared care with a GIC, whether based on a full GIC assessment or on the basis of a ‘harm reduction’ bridging prescription. These more knowledgeable GPs can then advise and educate colleagues in their own and neighbouring practices. Above all, both service users and GPs involved in these regional clinics were enthusiastic about how they brought HRT for trans people into the mainstream of primary care. Doctors in the regional clinics helped service users deal with a range of health issues, and hormone therapy came to be experienced as part of primary care, rather than something specialised, difficult, or in any way stigmatised.

The Welsh model is still far from perfect. However, it proves that there is no need for NHS England to keep asking the same tired questions and presenting the same tired answers. Yes, we deserve better than the Levy Review: but more importantly, positive change is both realistic and possible.