In May 1988, the Conservative government introduced Section 28. This legal measure outlawed support for “homosexuality as a pretended family relationship” across Britain, especially in schools. While Section 28 was eventually repealed between 2000 and 2003, it has had a long legacy of harm. Most LGBTIQ+ people who lived through it have never forgiven the politicians responsible.

In February 2026, following a similar pattern of escalating moral panic and extremist rhetoric against trans people (including non- binary people), the Labour government looks set to introduce its own version of Section 28, in the form of proposed revisions to the guidance on “keeping children safe in education” in England. These proposals seek to erase trans children: through extreme restrictions on social transition, toilet and sports bans, and censorship of the word “trans” itself. Like Section 28, they will most likely also create a wider chilling effect, reducing support for lesbian, gay, bi, and gender-nonconforming young people as well.

There are some important differences between the situation in the 1980s and today. Section 28 provided a strong rallying point for action in part because it was a single, explicitly homophobic, and powerfully impactful legal clause. Labour’s transphobia has been a lot more piecemeal, and complicated by an endless series of messy court cases, including this week’s extremely unclear High Court ruling on proposed segregation measures in the workplace and public services. Meanwhile, many Labour politicians continue to claim that they oppose transphobia, even as they support the most actively transphobic government in British history.

It is for this reason that we need to be loud, clear, and explicit about the active danger posed by Labour government policy. And this danger is explicit in the new proposals for “keeping children safe in education”.

What is the new schools guidance?

“Keeping children safe in education” is statutory guidance for schools in colleges in England. As “statutory” guidance, the document effectively operates as part of English law. It is regularly updated by UK governments, and the Labour government is now consulting on proposed revisions for 2026.

It is these proposed revisions that pose a threat to the safety of young trans people.

Importantly, this is not the same as the draft non-statutory guidance on “Gender Questioning Children” introduced by the Conservative government in late 2023. That guidance was not law, and was never formally adopted by the government – although in practice, many schools changed their policies and practice because of it.

However, Labour’s new proposed revisions to the guidance on “keeping children safe” are clearly influenced by that Conservative document, as well as the Cass Review, and the 2025 anti-trans Supreme Court judgement in For Women Scotland vs The Scottish Ministers.

In 2023 I outlined some key issues with the Conservative guidance. Here are those points, with notes on what has changed or been kept the same, as Labour seek to bring the Tory proposals into law.

- Trans students are presented as an implicit danger to themselves and others. This is still effectively the case in the 2026 proposals, which position a young person coming out as a major safeguarding issue.

- Schools are told to out trans students. This is still effectively the case in the 2026 proposals, which ban measures to protect trans students’ privacy (see toilets and changing rooms) and encourage schools to tell parents if their child is is “questioning their gender”.

- Schools are encouraged to intentionally misgender students. This is still effectively the case in the 2026 proposals, which draw on the Cass Review to discourage support for social transition.

- Schools are told to ban trans girls from girls’ toilets and changing rooms, and ban trans boys from boys’ toilets and changing rooms. This point is made even more strongly in the 2026 proposals, which draw on the 2025 Supreme Court decision to call for a complete trans toilet ban.

- School uniforms should be worn according to “biological sex”. This is one of the few Tory proposals which has been dropped from the 2026 proposals. The new proposals instead state that schools and colleges “should consider adopting policies across school and college life that maintain flexibility and avoid rigid rules based on gender stereotypes”.

- For sports, schools are told to “adopt clear rules which mandate separate-sex participation”. This is still the case in the 2026 proposals, which explicitly ban participation “in sports designated for the opposite sex”.

- The guidance entirely ignores legal protections for young trans people. This is almost entirely the case for the 2026 proposals, which acknowledge possible Equality Act protections on the grounds of “gender reassignment” in one short footnote.

- The guidance does not actually use the word “trans” once. This is still the case in the 2026 proposals. Young trans people are instead referred to as “gender questioning“. The document also uses the term “LGB” instead of “LGBT”. The language of trans or non-binary identity and experience is entirely erased.

Safeguarding and risk

“Keeping children safe in education” is a safeguarding document. The idea of the guidance is to manage risk, and help prevent harm to young people. Yet the Labour government’s proposed changes will have the opposite effect.

Discrimination and exclusion hurts people, especially young people. If implemented, the new guidelines will ensure that schools cannot possibly be an affirming or safe space for young trans people. This will be especially dangerous for the many young trans people who do not have a safe home environment, due to the transphobia of their parents, carers, or guardians. My own research has shown how an absence of affirmation can put young trans people at risk of sexual exploitation and statutory rape. These risks can be mitigated where people are able to socially transition in a safe, supportive environment.

This leads me on to the biggest issue with the proposed guidelines: their fearmongering and misinformation around social transition.

Social transition

Social transition describes a range of things a person might do to affirm their own gender. These things might include: a change of clothes or haircut, a change of name, and/or a change in pronouns. Social transition describes a series of choices that are linked to coming out as trans or otherwise gender diverse (e.g. non-binary, genderqueer, genderfluid). Social transition can also be a stage of experimentation or questioning, where young people figure out what is right for themselves. The changes we make may be temporary, or permanent: but regardless, these are deeply personal decisions.

In the Labour government’s proposed changes to the “Keeping children safe in education”, social transition is represented as a problem. The document recommends that “Schools and colleges should take a very careful approach”, and that “Primary schools should exercise particular caution, and we would expect support for full social transition to be agreed very rarely”. It further states that “a [school’s] decision relating to social transition may not be the same as a child’s wishes”.

This guidance is justified through reference to the final report of the Cass Review, a document which pathologises social transition by insisting that it should only be undertaken with medical guidance. This recommendation is as dangerous as it is offensive. Social transition is a personal decision linked to coming out. Doctors should have no role in deciding how someone dresses, or what name or pronoun they use.

The Cass Review has been widely discredited and condemned globally by researchers, medical practitioners, and community groups with relevant experience and expertise. This is in part because its most controversial recommendations are informed by pseudoscience and misrepresentation of evidence. For example, the Cass Review found no actual evidence of harm caused by social transition. Instead, it positions transition as a problem in and of itself. Its recommendations have been adopted as part of an eliminationist drive to erase trans existence entirely.

Speaking to the Metro this week, Dr Cal Horton, an expert in trans childhood, explained:

“Trans children need to be supported and respected in order to be safe at school, in order to access their right to education, in order to enjoy their childhood. Instead, we are seeing a complete ban on access to appropriate toilets, PE, accommodation on school trips, a complete erosion of their rights. It will lead to children avoiding the bathroom, avoiding exercise, missing out on school trips, dropping out of school, losing any hope of education, equality, friendship, happiness.”

I agree with Dr Horton. Furthermore, I believe these are the intended outcomes of the new Labour government proposals. As with Section 28, young people are presented with a choice between state-mandated abuse, or staying in the closet. The overall aim is to stop trans children from existing altogether.

As with Section 28, these hateful guidelines will never fully succeed in their aims. If implemented, they will certainly cause enormous harm. Yet trans kids are powerful and know their own minds, and many will continue to come out.

It is incumbent on us to fight with them for liberation.

Act by 22 April

We have two months to fight back against the Labour government’s new Section 28, as a consultation on the proposed guidelines is open until Wednesday 22 April.

One of the most obvious things you can do is respond to the consultation. This will likely be a long and discouraging process, so if you choose to respond, I encourage you to give yourself as much time as possible to work on it. There will also likely be consultation guidance produced by organisations such as Trans Actual and Gendered Intelligence. I will update this post as soon as that is available.

You can find the UK Government’s consultation page here. Note that they are consulting on a series of wider changes to the “Keeping children safe in education” guidance, not just the section on “gender questioning children”. Scroll to the bottom of the page for consultation document, full draft guidance, and a summary document.

At the same time, you may quite reasonably distrust government consultation processes at this point. I know I do. The consultation on the EHRC’s trans segregation plans last summer received approximately 50,000 responses, which were fed into AI instead of being read by human beings. If media reports from the likes of The Times are to be believed, the EHRC then simply produced the same hostile guidelines they were planning to all along.

Fortunately, there are a lot of other things you can do to oppose Labour’s new Section 28, including:

- Writing to your MP

- Organising against the proposals within your union

- Organising against the proposals with other parents or students

- Asking your local school’s headteacher or board of governors to speak out against it

- Banning the Labour Party from your local Pride (if they’re not already banned!)

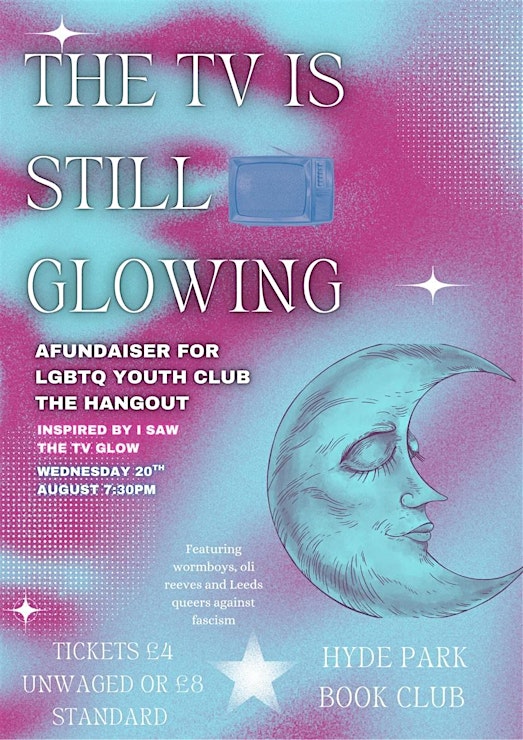

- Supporting trans youth groups

- Supporting youth-led campaign groups, especially Trans Kids Deserve Better

- Planning or supporting protests against the Government, Department for Education, and Labour Party

I’ve written about these ideas and more in two previous blogs posts. Both are also available as downloadable zines, so feel free to share these freely, either as PDFs or through printing them out and sharing them around.

- New Year’s Resolution: Smash the new Section 28 (2024)

- But what can I do? How to fight the trans panic (2025)

I am hoping to update the first one at some point to more explicitly address the latest proposals. However, I am not realistically sure when I will have the time or capacity. You are therefore welcome to create your own updated version too if you want, as long as you don’t sell it for profit, or misrepresent any of my original words or messages.

If you seek to understand criticisms of the Cass Review, or collate evidence for sharing others, I am maintaining an ever-growing roundup of academic research, commentary from medical experts, and statements from community groups here:

…and if we fail?

The original Section 28 was met with a storm of protest. LGBTQ people rallied across the UK. Ian McKellen came out as gay on live radio to speak out against it. Lesbian activists disrupted the BBC news, and abseiled into the House of Lords. The campaign group Stonewall was founded to oppose the new law.

None of this succeeded in stopping Section 28. But it did provide the initial momentum for a long, gruelling, yet eventually entirely successful campaign for its repeal. In the process, an entirely new wave of campaigning groups and activists emerged – including Queer Youth Network, where I cut my own teeth as a young campaigner.

The Conservative Party, meanwhile, never fully shook off the legacy of Section 28. They are still distrusted by many queer and trans voters for the harm they caused to entire generations.

If the Labour Party similarly proceeds with its plans for trans segregation and erasure in schools and beyond, we must never forget. Their legacy will be one of bigotry and hatred – and it is up to us to ensure their policies fail.