This post is about the Department for Education’s December 2023 draft guidance on “Gender Questioning Children”. Advice on how you can take action can be found at the end. You can download a printable zine here.

The post was updated on 23 February 2024 to add information on the Further Education Residential Standards Consultation and the murder of trans student Nex Benedict in a school toilet.

Like many other young people, my first experience of sexual assault was in school.

I stood in the lunch queue at my school’s canteen, a boy my age behind me. Unexpectedly, he began to tenderly caress my back and my bum. Feeling extremely uncomfortable and vulnerable, I turned to confront him. He leered, laughed, then accusingly asked, “you gay?”

Like many queer students during the 1990s and 2000s, I was bullied viciously throughout my time in school. I was teased incessantly, beaten up, and on one occasion knocked unconscious in front of my entire year group. Later, since I started living as a girl, I’ve been groped by men many times in clubs and pubs. Yet that specific moment of abuse sticks with me especially.

So much can be said about it. I was a heavily closeted trans girl attending an all-boy’s comprehensive, and yet to admit I was also bisexual. I wonder of course about the sexuality of my harasser, who may have found bullying the only “safe” way to experiment with his own desires. But most important is the context of the wider school environment. Homophobia and ignorance about sexuality and gender was the norm; one that was not simply enacted between children, but also deeply rooted in policy and law.

Nothing was ever done about this sexual assault – in part because I didn’t for a moment consider telling anyone.

I attended school at the time of Section 28, a notorious anti-gay law enacted across Britain by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. Section 28 was named for a clause in the Local Government Act 1988, in which local authorities (responsible for the management of state schools) were prohibited from “promoting homosexuality by teaching or by publishing material”, or promoting the “acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”. It was introduced following a major moral panic in the media over homosexuality in the wake of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, plus the publication of a handful of short books and leaflets with advice on teaching young people about the existence of gay and lesbian families or historical figures.

Section 28 would remain in force for over a decade. It was eventually repealed by the first Scottish Parliament in 2000, and in England and Wales by Tony Blair’s second Labour government in 2003, although its effects would linger for years to come. In addition to directly barring local authorities from introducing affirmative teaching material about lesbian, gay, and bi lives, Section 28 had the wider impact of stifling any real discussion around sexuality or gender difference. Teachers were afraid to talk about the issue, and books were banned from schools and libraries. Meanwhile, “gay” was the ultimate insult in the playground, a go-to word for any person, action, or object that was undesirable or bad.

Section 28 did not have anything specific to say about acknowledging that lesbian, gay, or bi people exist, or about homophobic bullying in school, let alone about trans or intersex matters. It didn’t need to. The vague prohibitions of the law, along with a more general culture of ignorance, silence, and fear promoted by politicians and journalists, meant that many people were uncertain where the boundaries of legality lay. Instead, there was a widespread feeling that you simply couldn’t talk about it.

The impact on entire generations of young lesbian, gay, bi, trans, intersex, and queer (LGBTIQ+) people was horrific. Many of my peers talk about the traumatic impact of growing up during this time, of struggling to come to terms with their desires and experiences, of failing to receive protection from adult authority figures or being abused directly by them. You can read more about this in accounts such as in Kestral Gaian’s book Twenty-Eight.

The worst thing for me about growing up under Section 28 was the utter lack of information. When it came to my sexuality and trans experience, I didn’t even know what I didn’t know. I had no easy way into understanding my own feelings and changing body, let alone the quiet but immense impact of a law I’d never heard of. I wrote a diary across several years chronicling my self-hatred and feelings of being ill, broken, wrong, a freak. I was extremely unusual in coming out as a girl during my teen years, in part because I had the luck to stumble across supportive US-based internet communities when I was 15, circa 2002. I wonder what information and support my harasser in the lunch queue ever had available to him.

The first adult I came out to outside of the internet was our Religious Education teacher, Mrs Richards. In retrospect, she was clearly a rebel, with a deep sense of Christian conviction about social justice which meant she was prepared to risk her job to do the right thing. At the time, I was vaguely aware she had been in trouble with the headteacher for telling a sex education class that, statistically speaking, at least some of us were gay and we needed to be okay with that. I told her that I wanted to be a girl, and asked where I could find help.

Mrs Richards did the best she could for me at the time – she sent me somewhere safer. She said she couldn’t speak with me, but recommended a free counselling service in town. This provided the first supportive, affirmative space in which I could explore my gender in person, laying the groundwork for my eventual transition. At the same time, I regret that even the most rebellious teacher in my school didn’t feel she could even safely listen to or reassure me in an extremely vulnerable moment.

After Section 28

Following the repeal of Section 28, many teachers remained unsure about what the law said and whether they were allowed to discuss LGBTIQ+ issues in the classroom. Nevertheless, there has been a gradual shift towards the explicit acknowledgement and inclusion of queer lives in curricula and pastoral support structures. In 2005, Schools Out launched the first LGBT History Month resources for schools. In my mid-20s, now a proudly out trans activist, I attended an event in Coventry about moving on from the legacy of Section 28. It was supported by the city council and attended by many teachers. A few years later, attempts to reintroduce Section 28-style policies at some academy schools were explicitly condemned by the Department for Education. The world was changing.

Meanwhile, LGBTIQ+ adults and young people were more visible in society than ever before. We were increasingly present on TV, in movies, and in the charts. The emergence of social media meant we began to find one another and create our own content on Myspace… then Facebook, Youtube Tumblr, Twitter, Twitch, and Tiktok. It became more normal to have an LGBTIQ+ friend, colleague, sibling, child, uncle, or parent. This created a virtuous cycle: the more we were out and visible in society, the easier it was to come out. There are now more openly lesbian, gay, bi, and trans young people in the UK than ever before. I hear about this a lot from friends who teach in secondary schools. Queer kids are increasingly just a normal part of school life. For those who need more support – often young trans people – there are often clubs or groups facilitated by teachers: something that would have been almost impossible under Section 28.

The new moral panic

Social progress is never linear nor guaranteed. We must therefore always be prepared to defend the gains we have made.

Since 2017, the UK has been gripped by a wide-ranging moral panic over trans people’s existence, as part of a wider backlash to social progress which has also affected groups including migrants, racalised minorities, and LGBTIQ+ people more widely. One element of this has specifically targeted educational, pastoral, and media support for young trans and gender non-conforming people. Prominent anti-trans campaigners have sought to raise fears over the growing number of out and proud young trans people, portraying trans experiences as a “social contagion” among children and adolescents, arguing that this should be addressed through the “elimination of transgenderism” or otherwise “reducing or keeping down the number of people who transition”.

The violence of this language is reflected in the violence that too many young trans people continue to face from other children and adolescents, as well as the adults who are supposed to help them. But anti-trans campaigners continue to position young trans people themselves as the problem. 2020, Liz Truss (then Women and Equalities Minister) stated that trans people aged under 18 should be “protected” from “decisions they could make“, raising fears of a new Section 28.

That new Section 28 is now here, in the form of draft non-statutory guidance on “Gender Questioning Children” for schools in England, produced by the Department for Education at the behest of the UK’s Conservative government. This document, which is currently under consultation, threatens to significantly undermine the ability of young people to safely be themselves. And just like Section 28, while the draft guidance specifically targets one group, it threatens to cause harm far more widely.

What does the Department of Education guidance say about “Gender Questioning Children”?

I will not be providing a detailed breakdown of everything the guidance states – for this, I recommend alternative analyses such as Robin Moira White’s excellent commentary for TransLucent. However, key elements include the following:

- Trans students are presented as an implicit danger to themselves and others. Schools are told to “safeguard” against young people coming out or transitioning, and the impact of this on other students.

- Schools are told to out trans students both to their parents and to the “school community”. The guidance prioritises informing others over young people’s own right to safety, confidentiality, or self-determination.

- Schools are encouraged to intentionally misgender students. Secondary schools are advised to consult parents and “only agree to a change of pronouns if they are confident that the benefit to the individual child outweighs the impact on the school community”. Primary schools are told that “children should not have different pronouns to their sex-based pronouns used about them”.

- Schools are told to ban trans girls from girls’ toilets and changing rooms, and ban trans boys from boys’ toilets and changing rooms. The guidance advises that toilets access should be based on “biological sex”, with the possibility of an “alternative changing or washing facility” for individual students given special dispensation.

- School uniforms should be worn according to “biological sex”: that is, trans girls are expected to wear boys’ uniforms, trans boys are expected to wear girls’ uniforms, and non-binary people are expected not to exist.

- For sports, schools are told to “adopt clear rules which mandate separate-sex participation” where “physical differences between the sexes threatens the safety of children”.

- The guidance entirely ignores legal protections for young trans people,most notably through excluding any discussion of “gender reassignment”, the category under which people who socially and/or medically transition are protected in the Equality Act 2010.

- The guidance does not actually use the word “trans” once (let alone non-binary). The very language we use to describe our own lives is excluded from the document. Instead it refers to children being “gender questioning”, “gender distressed or confused”, experiencing “gender incongruence”, or “gender dysphoria”, or undergoing “social transition”, implying that this occurs as the result of a contested “ideology” or “belief.

In short, the proposed guidance aims to position young trans, questioning, and otherwise gender non-conforming people as a problem. If implemented, it would make it extremely difficult – if not impossible – for young people to be themselves in school, to trust teachers, or to seek support if they are subject to transphobic bullying from peers. As Gendered Intelligence observe, “What strikes us most about this guidance is the tone of cruelty and contempt towards children and educators throughout.”

How dangerous is the Department for Education guidance?

In this post, I invoke the legacy of Section 28 very deliberately. The new proposed guidance on “Gender Questioning Children” is of course a very different document, produced in a different time, with a different response from civil society. However, I feel that understanding the guidance’s similarities to Section 28 is useful for analysing why it is so harmful, and understanding its differences can help us to map routes to resistance.

Like Section 28, the draft guidance is most dangerous in its vagueness. It does map out numerous ways to directly abuse young trans people, for example, through intentional misgendering and seeking to block social transition. However, it is the more general refusal to engage with the humanity and agency of young trans people – for example, through failing to even use the word “trans” once – which is most chilling.

While young trans people are of course the main target of the guidance on “gender questioning children”, the impact promises to be wider. As my own story shows, while Section 28 only explicitly targeted “homosexuality”, teachers or bullies didn’t tend to draw any distinction between gay, bi, queer, or trans experiences. Indeed, the atmosphere of ignorance and uncertainty made it difficult to event come to term with those differences. Many of us who went to school at that time struggled to come out because we had very little context for understanding ourselves. At my school, like many, boys were punished for painting their nails or growing hair past their neck. Similarly, the new guidance threatens to make life more difficult for any gender-nonconforming young person, regardless of whether they identify as trans. The point is to shore up and reinforce traditional understandings of sex and gender, in line with hardline conservative ideologies. Teachers, administrators, governors, and academy sponsors who actively wish to reinforce gender roles and make queer people’s lives more difficult will gain a powerful tool to legitimise sexist and homophobic policies, as well as transphobia.

However, homophobic bullying and ignorance also prospered under Section 28 because teachers were unsure about the limitations of the law and afraid to overstep. The new guidance’s insistence on entrenched biological essentialism could make even sympathetic teachers feel afraid to acknowledge queer and trans lives in their teaching, or otherwise put them under pressure from headteachers and governors. The whole point is to make LGBTIQ+ and especially trans students an impossibility: to enable incomprehension, to make them feel unwelcome, to “reduce” them in number, to make them disappear.

Where young queer and gender non-conforming people refuse to comply with this imperative to disappear – through coming out, through transition, through stubborn persistence – the guidance aims to make their lives immensely more difficult. They are to be outed to their peers, to their parents, to their peers’ parents. They are to be banned from wearing clothes associated with the “other sex”, barred from toilets and changing rooms, discouraged from using their own name and pronouns.

If enacted, this intentional targeting of trans and gender non-conforming lives and wellbeing will send an important message: it’s open season on the queers. As with Section 28, the guidance risks empowering bullies through fostering an atmosphere of institutionalised disrespect. The guidance states that “bullying of any child must not be tolerated”, but that statement feels pretty meaningless when the same document encourages schools to identify some children as different to their peers, and refuse their self-expression.

Normalising transphobia is extremely dangerous. We can see this, for example, in the murder of Brianna Ghey, a 16 year old trans girl who was stabbed to death in 2023 by two of her peers from school. Like many transphobic killings, her murder was extremely brutal. Prior to her death, the murderers shared numerous graphically violent messages about Brianna, using transmisogynist slurs and referring to her as “it”. This language and dehumanisation directly reflects discourses in society promoted online and in the press by gender-critical activists, journalists, and politicians from every major party. Brianna’s killers may have held the knife, but others with more power have repeatedly called for the “elimination of transgenderism”, and continue to do so.

Edit: 23/02/24 –

Two recent events have further highlighted just how dangerous the Department for Education “Guidance for Schools and Colleges: Gender Questioning Children” really is.

Firstly, the Department for Education has quietly introduced a second consultation. This consultation is on a proposed change to the actual law for Further Education colleges providing residential accommodation for students aged under 18. The law currently states that sleeping accommodation should “provide appropriate privacy for all students”. The Government is proposing to replace this with a clause requiring that “gender questioning students” either be segregated and made to sleep in a room on their own, or otherwise forced to share a space with students assigned the same sex at birth, as “different legal sexes should not be sharing sleeping accommodation”. This intervention shows how the main guidance is just one part of a wider attempt to undermine young trans people’s dignity and safety.

Secondly, just days ago Nex Benedict, a trans student in the US state of Oklahoma, was murdered by cis girls in the school toilets. Nex and another trans student were violently assaulted just months after their home state introduced a law requiring all students to only use toilets that match the sex listed on their birth certificate. This horrific killing reflects what researchers have been telling us for years: trans and gender non-conforming people of all genders are most at risk of violence in gendered spaces, and enforcing strict rules only exacerbates these risks.

The good news

It is difficult to feel positive in the current moment. After years of anti-trans campaigning and threats, the Conservative party is acting to intentionally make life harder for young trans people, in a move that has far wider implications for student safety as well as queer and feminist initiatives in schools. The Department for Education’s proposed school guidance is not simply being championed by the Conservative government – its publication has been “welcomed” by the Labour party, and supported by liberal media outlets such as the Observer as well as the Tory press.

However, the legacy of Section 28 is once again useful for understanding what is happening here. The Conservatives are once again showing us who they really are – this is not new. The Labour leadership were just as useless in responding to the original Section 28, and the UK Labour government was in power for six years (most of my time in secondary school!) before they bothered to repeal the law in England and Wales. The liberal media was somewhat more opposed to Section 28 in the 1980s than they appear to be now, but ultimately it was neither journalists or politicians who created the pressure for repeal. It was LGBTIQ+ campaigners and our allies: especially young people from groups such as Queer Youth Network who worked ceaselessly to change the conversation and create a better environment in schools and beyond.

Moreover, there are two major differences between 1988 and 2024 which are important to highlight.

Firstly, the legal situation is radically different. Section 28 was written into law, and applied across Britain. By contrast, the new guidance is “non-statutory”, and applies only to England. This means that schools are not legally obliged to follow it, especially in elsewhere in the UK. The government’s proposals can therefore be ignored. In fact, ignoring the guidance might even be the wisest option even for transphobes, given that the government’s own lawyers have warned that those who follow it risk breaking the law, as the recommendations appear to directly contradict both the Equality Act and elements of safeguarding legislation. Moreover, the guidance is yet to be published in its final form, as it is under consultation until 12th March – meaning that you can tell the government exactly what you think about it. Edit: 23/02/24 – however, since this post was written the government is now also seeking to change the law through the FE Residential Standards Consultation.

Secondly, there appears to be way more support for trans and gender nonconforming young people now than there was for young gay people in the 1980s, perhaps especially among teachers. The world has changed. For example, I learned about the government lawyers’ warnings from Schools Week. The very day the draft guidance was published, their main headline was Trans guidance: DfE lawyers said schools face ‘high risk’ of being sued. Individual teachers are speaking out across social media to voice their disgust and opposition to the proposals, and teaching unions have also expressed their concerns. Furthermore, headteachers such as Kevin Sexton from Chesterfield High School in Liverpool are going public with their opposition, noting that inclusive policies that centre actual safeguarding for young trans people have been working perfectly well for years. The school has no intention of scrapping its gender-neutral uniforms, mixed-gender sports, or all-gender toilets it provides to young people who need them.

As such, we are in a strong position to fight back against the new Section 28.

How you can take action

The original Section 28 was defeated because countless ordinary people took action. That can be the case again. Of course, some people are better placed than others to fight this particular threat to young people (for example, if you work in education in England). However, there will be things you can do regardless of who you are, how old you are, and where you live.

If possible, act with others, rather than alone. We are always more powerful together.

IDEA 1: Resist the new Section 28 in schools

If you are currently a student, a teacher, a parent or carer, a school administrator, a governor, or even working for an educational company or charity (e.g. in teacher recruitment) you are particularly well-placed to fight back against the new Section 28.

We can see inspiring examples of this in current protests by students and teachers in the US state of Florida, where the government has introduced a slew of anti-LGBTIQ+ laws, including a trans sports ban and a Section-28 style “don’t say gay” law. Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya wrote in Autostraddle about the power of student-staff solidarity in one Florida school:

I know a high school walk out sounds like a small thing, but this is huge. It shows a two-fold approach to resistance happening in the state: First, the administrators and staff members who flouted the ban in the first place showed it’s totally an option to just…not enforce transphobic regulations. If more Florida school staff were willing to do this, it would make the ban difficult and maybe even impossible to reinforce. Second, the students showed their solidarity and support not just for this one trans athlete but all trans athletes, holding signs and chanting affirmations of support for trans lives everywhere and questioning the ban. It’s further evidence that the Florida legislation does not adequately represent the Florida people.

Here are some ideas for English and Welsh schools:

- Non-compliance. As Upadhyaya observes, transphobic laws and guidance rely on people enforcing them. Headteachers, administrators, governors, and academy sponsors are of course in the best position to reject the new guidance should it be formally introduced following the government consultation. We can see this in the example of Chesterfield High School in Liverpool. But students and teachers can also take action, as can parents (regardless of whether or not your own child is trans). Anti-trans campaigners will be putting pressure on schools to enforce the new guidance, so every person who puts pressure on them to not do so will be important.

- Implementing alternative guidance. Robin Moira White notes that examples of good practice already exist for supporting trans students in schools and colleges. These include the Scottish government’s guidance on Supporting Transgender Pupils in Schools and Brighton & Hove City Council’s Trans Inclusion Schools Toolkit, both published in 2021.

Actions include:

- Refuse to implement the UK government’s guidance on “Gender Questioning Children” if you are in a place to do so, and instead follow the advice of e.g. the Brighton & Hove guidance.

- Write to the headteacher, Board of Governors, and/or academy sponsor, or ask for a meeting. Tell them that the school should ignore the UK government’s guidance and implement a better alternative. Highlight the danger posed to young people by the UK government’s proposed guidance, and the potential legal challenges the school may encounter if it follows that guidance.

- Hold a meeting of your own with other students, parents, teachers, and/or administrators. Discuss how you might work together for non-compliance and/or introducing or defending a better alternative.

IDEA 2: Pile on the political pressure

You don’t need to work or study in a school to make a difference. Countless other organisations are in a position to make a difference, and you can put pressure on them to do so. People living throughout the UK are potentially in a good position to do this.

Actions include:

- Write to your MP or councillor, or phone them up, or ask to meet them in person. Demand they put pressure on their party to actively oppose the UK government’s proposed guidance on “Gender Questioning Children”. This is particularly important for Labour representatives, as their party is likely to win the UK’s next general election.

- Write to your union and ask them to take a strong stance on opposing the proposed guidance, for example through public statements and/or taking part in the consultation.

- Write to local and national newspapers. Change the conversation by explaining why you think the government’s proposals pose a danger to the safe of young people.

- Ban the Conservative and Labour parties from Pride. In this post-Section 28 age, politicians love to use events such as Pride to boost their public image. If you’re not already involved in your local Pride, consider getting involved, or hold a counter-protest within the parade to ensure that transphobic politicians feel unwelcome.

- Stop giving money to transphobic media. Publishers such as the Guardian Media Group are always shilling for cash, claiming their journalism offers an important beacon of truth in a complex world. That’s not true if they’re constantly pushing hate. If a publication is publishing transphobia, don’t buy paper copies, don’t donate, don’t give them quotes or press releases, and at the very least install an ad block on your browser if you must keep reading.

IDEA 3: Take part in the consultation

I am less certain about this proposal than the others, but it is an obvious one to include. The UK government is holding a formal consultation on their proposed guidance for “Gender Questioning Children” in schools. Anyone can participate, and tell them what you think.

You can take part in the consultation here.

The upside of this is that it is an opportunity for us to speak back directly to the UK government and Department of Education. The downside is that there is a good chance we will be ignored. The past decade has seen more consultations on trans civil rights and healthcare than ever before – and overall, things have got a lot, lot worse. For example, a majority of respondents to the consultation on the Gender Recognition Act from both the UK and Scottish government supported reforms; those reforms are now thoroughly dead, at least for the time being. Trans communities have poured an enormous amount of time and energy into responding to malicious consultations when we could have been doing far more constructive things with our time.

However, in her post for TransLucent, Robin Moira White makes an important point. With the consultation closing on 12th March, the civil service may have little time to assess responses before a new general election is held. She therefore proposes that respondents request that the existing draft be “torn up and thrown away”, and new draft guidance be introduced, based on the Scottish and Brighton examples. If enough people and organisations argue for this, then it might put sufficient pressure on a new Labour government to do a better job.

A related approach was proposed by Edinburgh Action for Trans Health in response to an NHS consultation in 2017. They recommended “hostile participation in the form of direct submissions of demands that don’t react to the questions posed or restrict themselves to the scope imposed by the government”.

Actions therefore include:

- Take part in the consultation yourself, demanding the government scrap the proposed guidance and introduce something better.

- Encourage any relevant organisation you are part of to participate in the consultation (e.g. children’s and/or LGBTIQ+ charity, school, educational body, Pride organisation, university department) and ask for the same thing.

I won’t be producing any advice myself this time – instead, I hope this post will help people in thinking about wider routes to resistance. Edit 23/02/24 – However, the following guides have been produced by various organisations:

If you’re responding to consultations, don’t forget to also respond to the Department for Education’s deeply transphobic proposals regarding Further Education Residential Standards. This consultation closes 5 April 2024 so you have longer to respond.

IDEA 4: Support trans youth groups

Regardless of how things play out with the proposed guidance, young trans people are still having a hard time in schools.

There are a small handful of national bodies which support young trans people through advocacy and peer support: e.g. Gendered Intelligence, Colours Youth Network, and Mermaids operate across England. Perhaps more importantly, a lot of small, local youth groups exist specifically for queer and/or trans young people across the country. This was an unthinkable possibility when Mrs Richardson referred me to a local counselling service, so we really need to value and uplift these groups.

Actions include:

- Find out what youth groups exist locally where you are, and how you can best support them. Some groups will benefit from publicity in the local area; others will want to keep a low profile given the current atmosphere of transphobic backlash. Many will benefit from volunteers – not just to work directly with young people, but also to do jobs such as fundraising, running social media, or designing websites.

- Donate money. Pretty much every trans-oriented organisation will benefit from donations, especially those working with young people. If you can afford it, consider setting up a standing donation.

- Fundraise. If you can’t afford to donate, or want to do something more, you can do other things to raise money for trans youth organisations. Examples include: putting together a small gig, an art gallery, or a bake sale, or doing a sponsored activity.

IDEA 5: Plan a creative protest

Back in 1988, after the Conservative party introduced Section 28 and most Labour politicians refused oppose it, it would have been easy to despair. Instead, some extremely audacious actions took place in opposition to the law. Just after the House of Lords voted for the new law, members of the Lesbian Avengers abseiled into the debating chamber to protest it.

A few months later, another group of lesbian activists invaded a BBC studio during the Six O’Clock News, shouting “stop Section 28!”

While neither of these protests succeeded in blocking Section 28, they highlighted queer opposition to the new law, and inspired entire generations of new activists to fight back.

Actions include:

- Get creative. Find or create a group of like-minded individuals and think about how you can protest against transphobia. Consider how your action might best attract attention to the cause or put pressure on a group or organisation to change their position on the government’s proposed guidance. Think also about how you will keep yourselves and others safe.

There are no doubt a whole host of actions and interventions I haven’t thought of. We are never powerless, even in the face of entrenched fear and hatred.

—

So now it’s your turn: how will you resolve to smash the new Section 28?

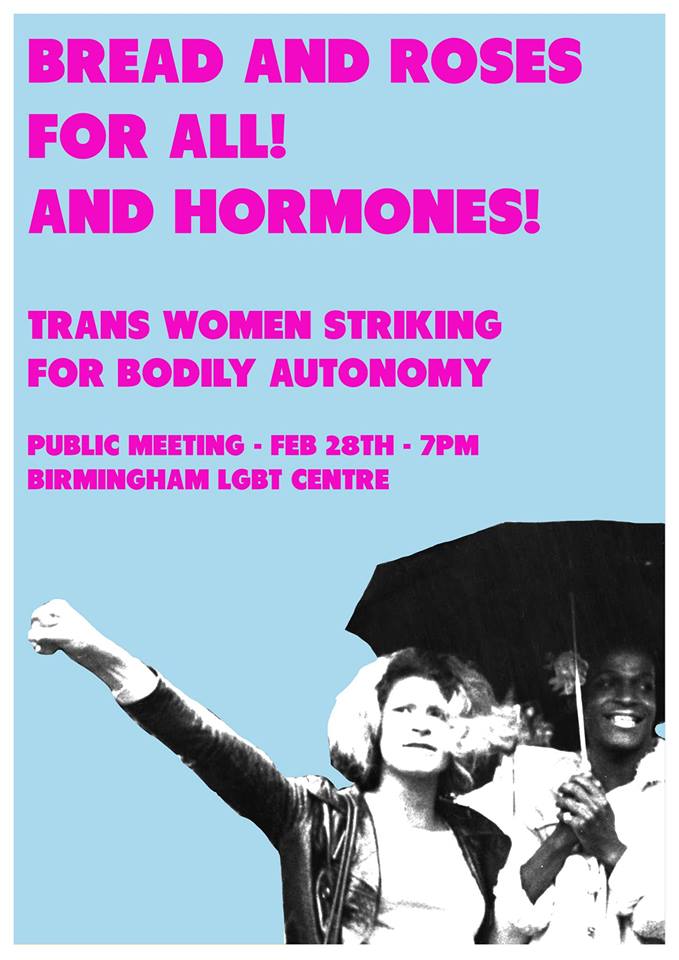

Wednesday 28 February

Wednesday 28 February