LGB rights charity Stonewall has a difficult history of engagement with trans issues. For 25 years the charity has been a powerful voice in the struggle for LGB equality, but ‘trans’ is not included in its remit within England and Wales. Stonewall has been criticised on one hand for this omission at a time when a majority of ‘LGB’ organisations have become ‘LGBT’, and accused on the other of undue interference in trans matters.

After years of misunderstandings and disagreement, Stonewall announced in June that it would be addressing these problems:

“At Stonewall we’re determined to do more to support trans communities (including those who identify as LGB) to help eradicate prejudice and achieve equality. There are lots of different views about the role Stonewall should play in achieving that. We’re holding roundtable meetings and having lots of conversations. Throughout this process we will be guided by trans people.”

I have been invited to a closed meeting that will take place as part of this process at the end of August.

I really welcome the proposal from Stonewall. In this post I’m going to explore why this dialogue is important, outline some of the proposed approaches to working with Stonewall (or not), and outline my priorities in discussing this issue with both Stonewall and other trans activists.

I also encourage readers to leave their own thoughts and feedback in the comments.

The current situation for trans people in England and Wales

I don’t feel it is an exaggeration to describe the current social and political climate as an emergency. Whilst it is true that trans people in the UK currently benefit from unprecedented civil rights, and there is talk of a “transgender tipping point” in terms of public discourse in the English-speaking world, many trans people still face very serious challenges in everyday life.

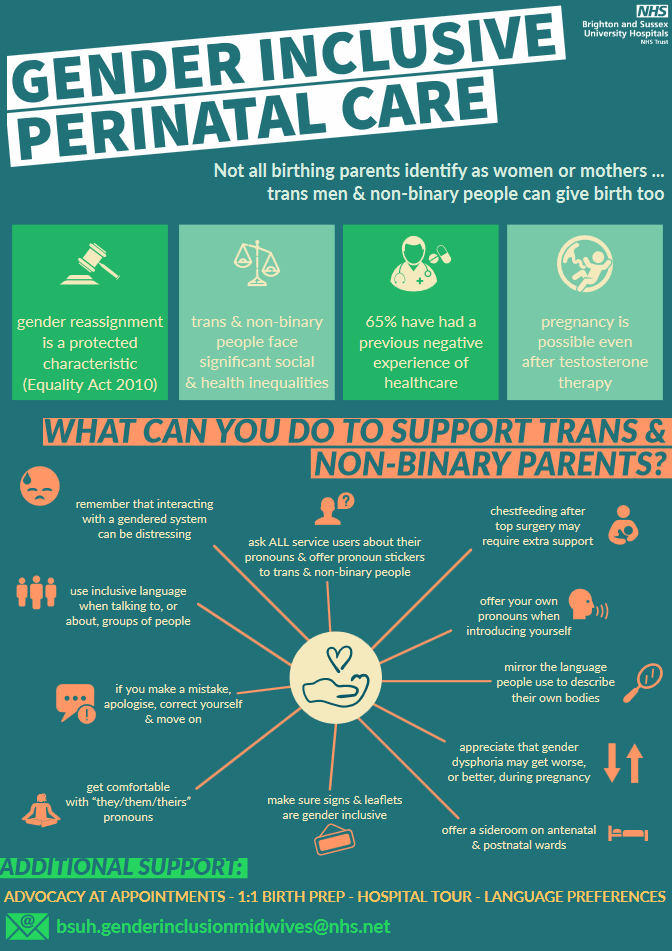

For instance, trans people are still likely to face discrimination, harassment and abuse in accessing medical services, as demonstrated in horrific detail by #transdocfail. Trans people are particularly likely to suffer from mental health problems, and this is often made worse by members of the medical profession.

For many years now there has been an exponential rise in the number of trans people accessing transition-related services; with cuts and freezes to healthcare spending from 2010, this has meant that many individuals now have to wait years for an initial appointment at at gender clinic. This problem has been compounded for trans women seeking genital surgery by the additional backlogs accompanying the recent resignation of surgeon James Bellringer.

Meanwhile, the impact of the Coalition government’s austerity agenda is being felt particularly keenly by less privileged trans people. With many continuing to face aforementioned mental health problem and discrimination from employers, benefit cuts and the increasing precariousness of employment and public demonisation of the unemployed are hitting hard amongst my contacts (some discussion of this in a wider LGBT context can be found here). Cuts to public services are also felt strongly by groups such as the disproportionate number of trans people who face domestic abuse.

Then there’s what we don’t know. For instance, research in the United States shows that young trans people are particularly likely to be homeless, and that trans women are considerably more liable to contract HIV than the general population. Both anecdotal evidence and extrapolation from international statistics and small local studies pointing to similar problems existing in the UK, but this is not enough evidence to properly address these serious issues.

Activism

I believe that trans people need a campaigning organisation that is up to the task of tackling the above problems. A campaigning organisation with the funding, resources and knowledge to lobby government, conduct research and push for social change.

Currently we rely on the energies of unpaid activists and ad-hoc organisations that are lucky to attract any kind of funding. The importance and achievements of organisations such as Press For Change and Trans Media Watch should not be underestimated, but this is not enough. Whilst Stonewall attracts millions of pounds in funding and wields an impressive range of resources, trans groups staffed largely by enthusiastic volunteers are lucky to land a few hundred pounds in donations, or a temporary project grant. You can probably count the number of trans activists employed to push for change in this country on your fingers.

Under such circumstances, stress and burnout are common amongst trans activists, even expected. Personality clashes are capable of sinking an organisation. The individuals most able to work long hours for free are typically the most privileged, meaning that there is poor representation in terms of race, disability and class.

We have to do better. We need to do better.

Solution 1: a new trans organisation

There will be those who wish to pursue the creation of a new trans organisation entirely separate from Stonewall. From this perspective, a dialogue with Stonewall offers the opportunity to discuss instances where the charity might have overstepped the mark in speaking out in relation to trans issues without this being within their remit. Beyond that, there will probably be a desire to ‘go it alone’.

For some, this will be because of Stonewall’s non-democratic structure (it is not intended to be a membership organisation), corporate links, and past disappointments such as the organisation’s initial refusal to campaign for same-sex marriage.

For others, this will be because of the view that the ‘T’ should remain independent of ‘LGB’. This position can be based upon the argument that the interests and needs of trans people differ to those of lesbian, gay and bisexual people, and/or a recognition that the trans liberation project is significantly less advanced than the LGB equivalent. From this also comes the idea that cis gay activists might not be able to properly campaign on trans issues.

There have been numerous attempts to create such an organisation over the last decade (one of which I was involved in, through Gender Spectrum UK) but none have been successful. I propose that one of the most serious barriers here is that of funding: there is so much work to be done and so many problems that individual activists are likely to face in their personal lives, that it has been extremely difficult for unpaid activists to put in the work necessary to launch such a body.

Solution 2: adding the ‘T’ to Stonewall

It has long been suggested that Stonewall should follow other LGBT organisations in becoming trans-inclusive. The arguments frequently centre upon an appeal to history, and the similarities of LGBT experiences.

The Pride movement emerged out of alliances forged between sexual minorities and gender variant people; this happened in part because homophobic and transphobic attitudes tend to stem from the same bigotry. Trans people have always been present in the struggle for gay and bisexual rights. Pretty much all LGBT people can talk about ‘coming out’, usually to family as well as friends, peers and/or colleagues. LGBT people often have to tackle internalised shame at some point in their lives, an inevitable outcome of growing up in a homophobic/transphobic world.

Moreover, with a great deal of organisations turning to Stonewall for LGBT equality advice and training, it has been argued that it only makes sense to explicitly incorporate trans issues, lest trans people get left behind. For instance, Stonewall does a lot of work on homophobic bullying in schools – surely it would make sense to also address transphobic bullying, particularly as the two tend to have a similar root cause?

Solution 3: a hybrid organisation

An idea I’ve heard bounced around a little ahead of August’s meeting is a kind of compromise between the two above positions. A trans charity that is linked to Stonewall in terms of sharing resources, information and funding, but remains semi-autonomous with its own leadership and trustees.

This is currently my favoured option. I feel that trans people would benefit greatly from effectively sharing some of Stonewall’s power. We’d certainly benefit from working more consistently together, instead of occasionally against one another. But we have different needs, different priorities. We might want to run our own organisation in a different way, and make somewhat different political decisions.

My priorities in the dialogue with Stonewall

1) Representation

I was actually a little bit uncomfortable to be invited to the meeting in August. Sure, I’ve been involved in plenty of both high-profile, national campaigns, as well bits of activism in my local area and place of work. Plus, a lot of people read this blog. But ultimately, I received an invitation because I have the right connections. So many didn’t get that chance. I also strongly suspect that the majority of people present at the meeting will be white and middle-class, and that there will not be many genderqueer people present (I’m less sure about disability, because there are a lot of disabled trans people).

I’m hoping that any future meetings will be more open. If it turns out that my suspicions are correct regarding the overrepresentation of privileged groups, I hope that we can take steps to ensure that any future meetings are more representative. It’s the only way we’re going to find a way to create consensus and work on the behalf of all trans people in the long term.

If you’re not going to be at the meeting, I strongly encourage you to respond to Stonewall’s survey so your voice is heard. Also, since I’ll be there in person, I’d really like to know what you think.

2) The creation of a new trans organisation

I’ve pretty much made the argument for this already. We need national representation that can genuinely address the many problems faced by trans people today. A democratically accountable body that reflects diversity of trans lives and experiences.

I hope this is something we can work towards by working with Stonewall. Yes, there will be political differences – certainly I have ideological objections to some of the approaches taken by Stonewall – but I feel the situation is too severe and the opportunity too important to reject an offer of help.

That isn’t to say that a new organisation should overrule the work of existing organisations. I would hope that any new body works alongside existing campaign groups such as Trans Media Watch, Gendered Intelligence and Action For Trans Health without seeking to duplicate their work.

3) Starting with the essentials

I believe that the initial basis for any new trans organisation – or trans campaigns within Stonewall – should be addressing the absolute, basic needs that are not currently being met for many trans people. Housing. Health. Employment. We should be looking out for the most vulnerable, as well as addressing universal needs. This is pretty much a moral duty.

What do you think? Please share your thoughts and ideas in the comments!