This is the fifth in a series of blog posts about the 2nd International Trans Studies Conference in Evanston (4-7 September 2024).

Read Part 1 here.

Read Part 2 here.

Read Part 3 here.

Read Part 4 here.

It’s difficult to put into words what an enormous experience the 2nd International Trans Studies Conference was: the power of being in community with other trans scholars, the benefits of sharing ideas across disciplines and borders, the frustrations that arose with technical difficulties and the academy’s complicity in so many forms of violence. I intended to reflect on some of these matters further in a final blog post, but for now suffice to say that I was by turns exhausted, joyous, and hopeful throughout the fourth and final day of the event.

On being a target: How trans studies scholars and practitioners can survive hate and harassment

Saturday morning featured a session I had put together, focusing on strategies for survival in trans studies at a time of increased negative attention on our work. I approached several colleagues who have encountered substantial challenges from anti-trans campaigns, three of whom kindly agreed to join me to talk about what we might do about this.

Asa Radix of Callen-Lorde Community Health Center (USA) and Samantha Martin of Birmingham City University (UK) were sadly not able to join us in person, but recorded brilliant videos describing practical and theoretical responses to their experiences of being targeted by hate movements, both externally and within the institutions in which they worked. Florence Ashley of the University of Alberta (Canada) brought their irrepressible physical presence to the room, exploring in a short talk how proposed police monitoring of their law classes threatened to undermine the academic freedom of their students.

I wrote my own short presentation based on my experiences, explaining the abuse and harassment that continues to disrupt my research, and ways in which I have sought to counter this in practice. Drawing on my 2020 article “A Methodology for the Marginalised”, I argued that it should not be our individual responsibility to look after ourselves. Rather, we need practical support from the employers who benefit from our work. We also gain from building communities and networks of mutual support among marginalised academics, both within and beyond trans studies. A copy of my slides can be found here.

For me the most important part of the session was not what the speakers said, however: it was the opportunity for attendees to discuss their own experiences and strategies for navigating institutional barriers and opportunities for support. Whereas most of the conference consisted of several academic presentations followed by a short Q&A, we intentionally structured this session to enable as much conversation as possible, with questions fielded by anyone and everyone in the room rather than just looking to the speakers as experts. As a lecturer in community development, I found myself almost surprised by the rigidity of the traditional conference format, and was glad that attendees felt they benefited from our more open-ended approach, and the opportunity to discuss and sit with ideas.

Sadly, our online attendees did not have the same experience as those in the room. Like many other sessions at the conference, ours was plagued with technical difficulties due to problems with the digital conference software Ex Ordo. Given this possibility, and the fact that our session featured two video presentations, I turned up early in the morning to strategise with our amazing technical assistant, Srishti Chatterjee. Unfortunately, the session before ours ended up overrunning due to their own technical issues, meaning that we no time to properly set things up. Under pressure, we managed to get the videos working, but weren’t able to monitor the online chat while this was happening, not realising until afterwards that they were not visible for those outside the room. It would have undoubtedly been worse if Srish was not present, highlighting the importance of having trained people with initiative on hand to respond to problems as they arise.

You can read a third party account of our session on Amy Ko’s blog (thanks Amy!)

Trans Synths and Synthetic Sounds

After our intense discussion of hate and safety, I sought refuge in a more joyous session. And so to synths, and synthetic sounds: to trans pop and hyperpop, music that brings me immense joy.

This session began with a talk titled Switched-On Reality: The Synthesizer and Trans Subjectivity, by Westley Montgomery of Stanford University (USA). Montgomery highlighted the enormous contributions to music made by two pioneering synthesiser artists: Wendy Carlos and Sylvester.

Carlos is famous for her arrangements of Bach for the Moog synthesiser, as well as her film scores for A Clockwork Orange, The Shining, and Tron. Sylvester was a member of the drag theatre group The Cockettes, before becoming known as the “Queen of Disco” with hits such as “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)”. Both are therefore remembered for their major contributions to 20th Century popular music, but as Montgomery observed, can also be seen as “bad trans objects”.

Carlos transitioned in the 1960s and disclosed her trans history in the late 1970s, following her rise to prominence. In this way she became an extremely high profile trans musician. However, she also distanced herself actively from trans liberation movements, enabled by her relative privilege as a highly educated, white, middle-class woman. Montgomery wryly observed that people have asked ‘“where was Wendy Carlos [who lived in New York at the time] during Stonewall?’”, noting that, “the answer is most likely at home, playing Bach”. Sylvester, a Black middle-class person with an ambivalent public relationship to gender, famously proclaimed “If I want to be a woman, I can be a woman. If I want to be a man, I can be one”. However, Sylvester actively rejected transsexual identification, was uninvolved in the civil rights movement, and would later also reject disco music as it waned in popularity.

Both Wendy Carlos and Sylvester can therefore be understood as assimilationist figures who do not live up to liberatory ideals. But Montgomery argued that they must be understood within the context of the material conditions in which they lived. Moreover, their musical contributions are historically significant regardless, especially in terms of synthesiser use. Montgomery posited that the mainstream emergence of the synthesiser and of women and queer musicians happened in tandem, enabling a resignification of womanhood. Montgomery ended the talk by Hannah Baer, who argues moreover that the synthesiser is inherently not cisgender: “a synthesiser’s shape is not in any way where the sound comes from, and there’s something so free and trans in that. You have no idea what sound is going to come out of this thing. And maybe I don’t either!”

The next few talks shifted the focus to 21st Century synthetic sounds in the context of hyperpop. In Gender Knobs: Transgender Expression through Vocal Filtering Technology in Drag, Hyperpop Music and Beyond, Jordan Bargett of Southern Illinois University at Carbondale (USA) looked at the gendering of voice through pitch filtering. Her story began with the vocoder, originally invented to extend bandwidth in telefony, and later adapted for encryption in World War 2 before being adapted for popular music by artists including Wendy Carlos and Laurie Anderson. Anderson in particular used pitch filtering for gender drag in “O Superman”, using it to perform a masculine “voice of authority”. In the 2000s and 2010s pitch-shifting gained popularity with nightcore, setting the scene for trans-specific experimentation within hyperpop.

With hyperpop, Bargett explained that filtered vocals could be used for more nuanced gender expression as well as drag. They introduced the examples of trans women artists SOPHIE and Laura Les, who both used pitch filtering to create more “feminine” singing voices. In this context, authentic trans voices might be understood as both “synthesised and authentic”. At the same time, Bargett cautions that pitch alone does not, of course, gender a voice, and that hyperpop artists tend to be well aware of this. She presented the example of SOPHIE’s music video “It’s Okay to Cry”, in which the artist’s voice and body are “undressed”: an expression of trans vulnerability. The talk concluded with a screening of Bargett’s own short film “Transistor”, which explored how “technology can be an extension of the trans self and body”.

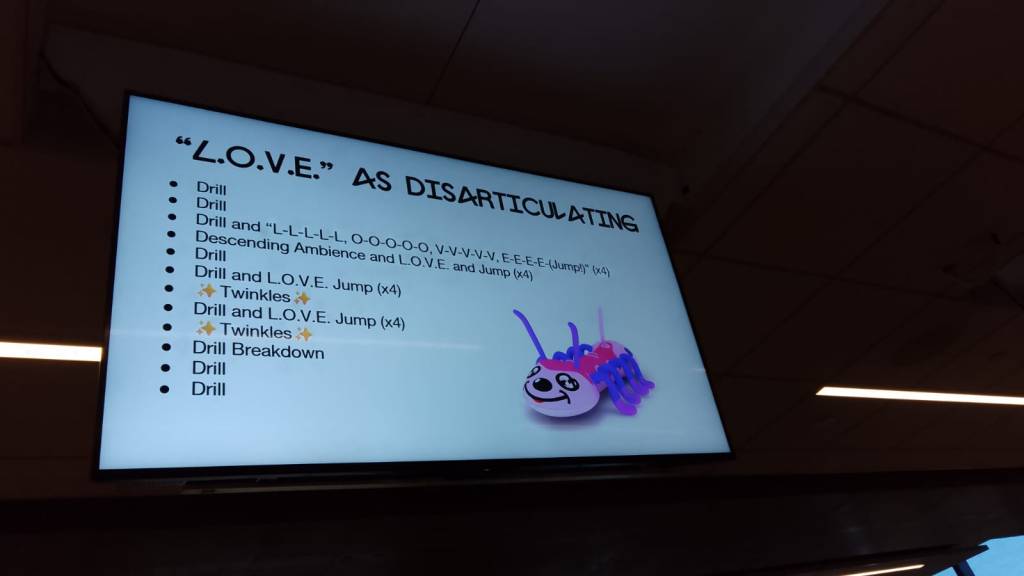

We heard more about SOPHIE from Gabriel Fianderio of the University of Wisconsin-Madison (USA), in Interpretation and articulation: Transphobia and Dysphoria Through SOPHIE’s “L.O.VE.”. Fianderio began by noting that “BIPP”, the opening track on SOPHIE’s debut EP PRODUCT, promises to make us “feel better”. But “L.O.V.E”, the closing track on the EP, is difficult to listen to due to the hostile noise of the dentist’s drill that recurs throughout the song. How to make sense of this disjuncture?

Fianderio posits that SOPHIE’s music provides a context in which we can move from “interpretation” (one truth) to “articulation” (space for multiplicity). Interpretation is often a problem with trans people. Citing Salamon, Fianderio noted that “trans panic” defences for the murder of trans women often depend on the interpretation of gender expression as “an aggressive act, akin to a sexual advance or sexual assault”. Similarly, dysphoria can entail a range of complex feelings and sensations relating to ourselves and others. Forms of interpretation centring pain, disgust, and distress ignores the complexity of ambivalence, and the possibility for accompanying euphoria.

Fianderio’s argument was that “L.O.V.E.” problematises interpretation through its use of the drill sound. They drew on internet commentary to show how the sound is often described by listeners as a physical experience (e.g. “This unblocks my nose”). Complex textures underlie this painful sound of the drill, and complex articulations are subsequently appreciated by listeners who spend time with the song and come to enjoy it. In this context, “L.O.V.E.”’s rejection of singular interpretation enables listeners to read conflicting emotions into the same form, and hence articulate complex feelings around euphoria and dysphoria. This can take place with and through the drill sound itself, and/or the song structure itself, with its synthesised vocals and moments of relief and beauty.

The final talk in the session, by Lee Tyson of Ithaca College (USA), was titled Trans Hyperpop and the Synthetic Authenticity of the Digital Voice. Tyson asked how and why trans hyperpop artists are positioned as “authentic”. Their talk began again with SOPHIE, noting that she was widely celebrated for her “authenticity” following her accidental death in 2021, which appeared to potentially contract with the experimental approach and ironic sincerity she employed in much of her music. Tyson describes this as a form of “synthetic authenticity” that can be found among many trans hyperpop musicians.

Tyson returned to the topic of vocal manipulation, quoting Laura Les’ comments on her earlier work, in which she explained she altered her vocals because “it’s the only way I can record, I can’t listen to my regular voice, usually” [my note: interestingly, the most recent material from Les’ band 100 gecs features much less processing on her vocals]. By contrast, Dorian Electra artificially inflates the character of their voice: “My music is simultaneously artificial and authentic. It’s just as authentic to use the same sappy love song language that’s been used in a million ways. A person singing a love song is still putting on a character”.

Tyson contextualised these comments by noting that voice manipulation can be understood as part of a wider technological field, as with (for example) hormone therapy, surgeries, and voice training. Within this field, hyperpop can be understood as a form of simultaneous deconstruction/reconstruction [note: I have also written on this as a feature of trans music!] This is not always liberatory: Tyson outlined the examples of the commercialisation of hyperpop, and the white appropriation of tropes of Black soul music by artists such as SOPHIE. At the same time, by finding something “more real” in artificial sounds, hyperpop offers a productive challenge to contemporary trans advocacy strategies and neoliberal imperatives of self-actualisation which rely on norms of intelligibility.

Overall, this was one of my favourite sessions of the conference. Like much of the music under discussion, it was self-knowingly silly and playful – yet stuffed full of surprising depth and interesting ideas. I only wish that the presenters had spent less time critiquing the whiteness of hyperpop, and more time considering the work of groundbreaking artists of colour such as underscores. Meanwhile, I don’t think music in and of itself can change the world, but it can help change the way we think, and that’s powerful and important.

Caucuses

After lunch, I spent most of the afternoon in a range of caucus sessions. These actually ran throughout the conference, and offered more open discussion spaces for people to have conversations on the basis of shared personal/demographic experiences or disciplinary interests. For example, there was an Asian scholars’ caucus, and a caucus for people studying trans healthcare.

Unfortunately, the schedule for the event was so jam-packed that each of the caucuses took place alongside multiple parallel presentation sessions. As such, I didn’t get around to attending any of the ones relevant or open to me until the final afternoon, when I managed to go to three in succession.

The first of these was the Palestinian caucus. This was an informal but very well-attended event arranged by attendees who wanted to organise collectively against the ongoing genocide in Gaza. This felt particularly urgent at the conference given the absence of Palestinian speakers, the presence of corporations who invest financially in the Israeli regime, and the suspension of Northwestern University professor Steven Thrasher following his support for a student encampment.

The second was the trans women and transfeminine scholars’ caucus. I recommended this take place and volunteered to chair it after a callout for volunteers from the conference organisers. Like many trans professional and trans studies spaces, the conference was dominated by men and transmasculine people. One joke often repeated at the conference was that “trans studies is mostly trans men who talk about trans women to cis women”: it felt very different to consider the repercussions of this within a woman and transfeminine only space. I found it very meaningful and refreshing to connect with colleagues in this context, and there is at least one very cool idea which might come out of our conversations, so watch this space.

Finally, I attended a caucus on publicly engaged scholarship. This turned out to be a small number of us swapping career advice, which is perhaps not what I originally intended, but felt very productive nonetheless!

Closing plenary

The conference closed with a plenary titled Whither Trans Studies? Towards a Future for the Field.

First, organiser TJ Billard took to the stage to make some closing comments. They thanked their fellow organisers, plus the conference’s steering group and sponsors, reflecting on how important it is that various university departments (especially at Northwestern) and research institutions support trans studies. They then reflected on the conference’s ambitious approaches to accessibility and inclusion, which faced some significant hitches in practice.

Billard thanked conference attendees for being patient and forgiving when things went wrong, and encouraged future organisers to “learn from the things that we tried to do, learn that the things that we failed to do, shortcomings both technical and intellectual”. They noted, echoing the complaints of the Palestinian caucus, that this included the absence of Palestinian scholars at a time of ongoing scholaricide, and apologised for the organisers’ failings in this regard.

We then heard reports from a small number of the caucuses. The graduate student caucus asked, “where is trans studies going? There was lots of discussion, and no consensus”. The Asian scholars’ caucus noted how the needs of Asian scholars are not necessarily met in “standard” Anglophone trans studies classes or syllabi, and reflected on the importance of building a network and not being alone.

The most extensive report came from the disabled scholars’ caucus, and these reflected many of the major strengths and failings of the conference I and others have written about recently. For many disabled scholars, we heard, this was a first opportunity to know of one another’s existence. Nevertheless, “the absences at this conference [were] as significant as the presences”: a comment that reflected Kai Pyle’s statements on the absence of Indigenous scholars in the opening plenary. Disabled people were absent due to numerous barriers to participation: this included the extreme circumstances facing those experiencing disablement through genocidal actions note just in Gaza, but also in Sudan and Congo.

In this context, the disabled trans scholars who were present were broadly “grateful and somewhat okay with the access we have experienced this week”. However, we were left with a number of thoughts which will be vital for future organisers: “Access is about justice, and justice is about accountability […] Access is not simply a matter of getting into a building. It is about interrogating why a building is inaccessible in the first place”.

Then the conference closed with a barnstorming final speech from the legendary Susan Stryker. She began by thanking all the people who had approached her throughout the event to thank her for her significant body of work: “I appreciate that something that I did landed with you in some way”. She then turned to think through the purpose and importance of trans studies.

Stryker started by looking to the roots of her own oppression. She explained that this has informed her analysis of body politics that positions people within specific, given social roles. She argued that while this body politics is a lynchpin of the Eurocentric social order, it has not always been this way, and it does not have to by this way.

What does it mean to be trans in this oppressive social order? Stryker proclaimed that “transness is an affective experience, driven by suffering and drawn by desire […] it is a practice of freedom”. This presents the possibility of alliance across multiple liberation movements. As Black trans studies has shown, transness is not just about sex/gender, but also at least as much about race, and the ways that certain bodies are racialised through gendering and gendered through racialisation. It is also vital that trans people understand their commonality with feminism. Insofar as feminism defies biological determination, “feminism can be considered a trans practice of freedom”. What brings us together is our movement across the boundary of categories designed to restrict freedom: “it is wrong to believe that embodiment must be a trap”.

Consequently, trans studies is about the pursuit of freedom, and should be a liberatory practice. Stryker cautioned us that creating an institutionalised form of trans studies does not solve the actual problems we face. She wryly insisted that we learn from the student movements of the 1960s, which did not achieve revolution, but instead “achieved ethnic studies departments”. She encouraged us to consider how we might use what positions we have in the academy to create space for struggle: “If we are so damn radical, if we are so dangerous, why has the field not been oppressed more brutally?” Stryker explained that she wasn’t trying to deny the real oppression we face – but rather, to acknowledge that as we sat gathered in the state of Illinois, certain things were possible for us which are not necessarily possible elsewhere.

At this juncture, Stryker reminded us of Stephen Thrasher’s suspension for visiting a student camp that supported the Palestinian struggle against genocide. She invited us to consider what it is about a trans studies conference – sponsored by the very institution that suspended Thrasher – that makes us more acceptable than voicing support for people facing death in Gaza?

Stryker shared several concerns raised at the Palestinian caucus with the rest of the conference, asking: what might a post-disciplinary trans studies look like in light of an absence of meaningful, substantive engagement with the genocide in Gaza? Drawing on a statement put together by the caucus, she noted that the conference was not BDS compliant, that attendees were not made aware of Northwestern University’s complicity in genocide, that there was no explicit discussion of the scholarcide in Gaza in the official programming, and that there was no formal engagement with the large Palestinian diaspora community living near to the campus. She argued that a shared liberatory goal for trans studies should include solidarity with Palestine, and future organising should undertake a good faith effort to foreground Palestinian scholars and be BDS compliant. Stryker invited scholars to raise their hands if they were supportive of these statements of solidarity: a majority of the room immediately did so.

Finally, Stryker formally proposed the creation of a new International Trans Studies Association, as a context for trans studies scholars to organise for freedom. As the “largest, most diverse gathering of trans studies scholars to date”, she stated her belief that the conference had a mandate to make a decision on the creation of this new association. She proposed that this process begin by taking advantage of the international steering group assembled for the 2nd International Trans Studies Conference, with this group invited to create proposed bylaws for the new organisation, and all conference attendees invited to join as founding members and vote on the proposed bylaws. Stryker asked if the room was in favour of this process, and asked us to raise our hands if so: once again, there was an overwhelming expression of support.

And that was it!

I’m really grateful to everyone who has written to say how they have found this series of blog posts interesting or useful. I think it’s really important to share material from conferences with people who are unable to attend. I used to regularly livetweet, but this no longer feels like a productive form of engagement. Writing up my notes ended up taking a lot longer than anticipated, and the length of some of these posts has felt a bit unwieldy. It’s also a bit frustrating to be finishing off the series over a month after the conference ended! Still, it feels really important to have some kind of record.

I’m hoping to write a final post on the Trans Studies Conference, reflecting more broadly on my experiences and questions of accessibility and resourcing, possibly comparing and contrasting with the 2024 WPATH Symposium in Lisbon. Let’s see how I do!